Latest News

Posted on March 3rd 2020

Critics Club - Breaking Down Gallery Walls

How do you make children feel at home in a museum?

On a wet Monday afternoon, a group of 13 and 14-year-olds from Harris Academy Peckham have been ushered into the Royal Academy of Arts in London. “So is there art . . . everywhere here?” one asks. They all stare, wide-eyed, at the ceiling. High up, three nude Graces are unveiling a personification of Nature with a bewildering number of bared breasts.

These 13 children look like a perfect snap shot of ethnically diverse, modern Britain. Yet they are far from representative of the gallery-going public. Although they are bright, enthused and at a school just a single bus journey from the gallery, none has been to the Royal Academy (RA) before. For some, it is their first time inside an art gallery of any kind.

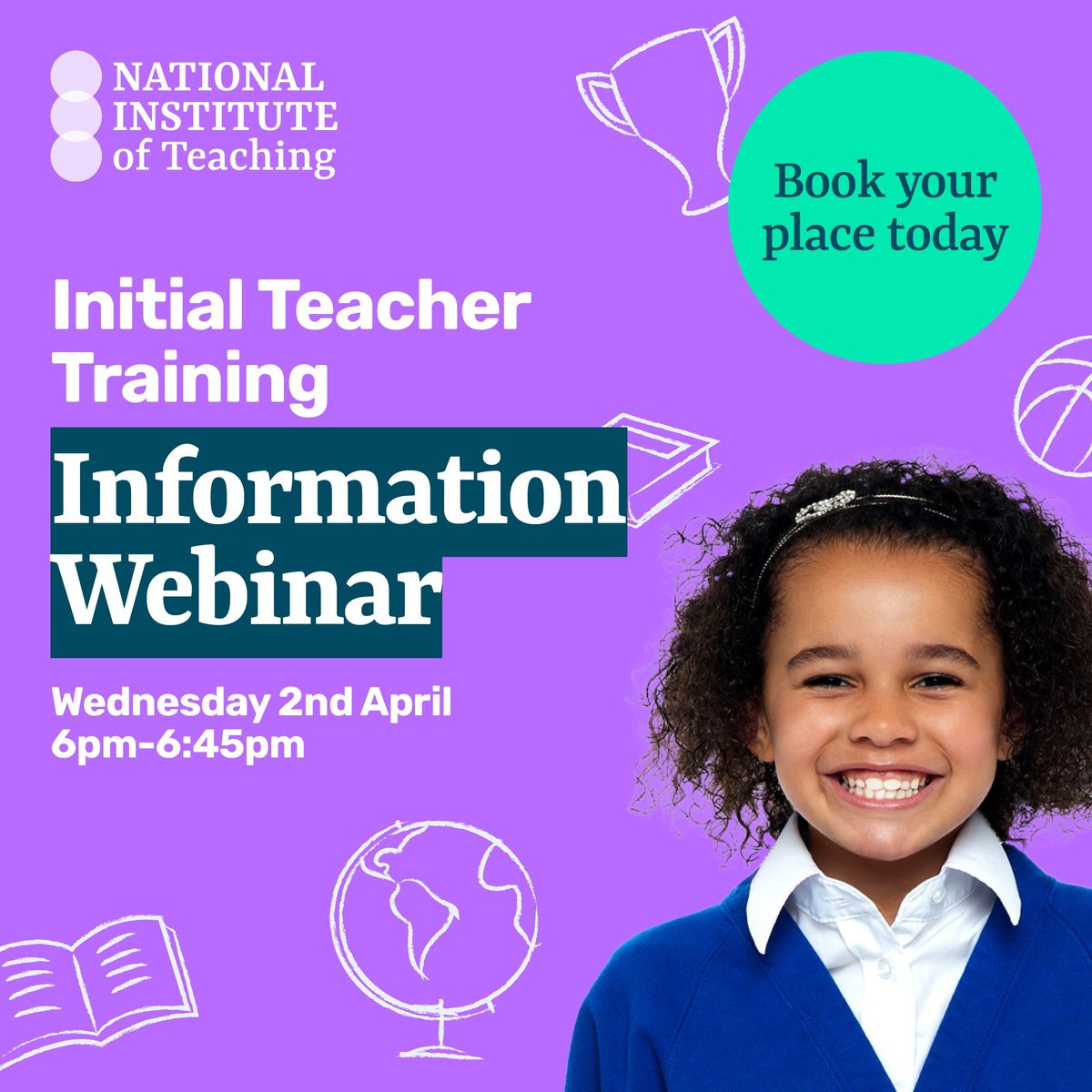

Students enjoy the Eco-Visionaries exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts.

“It’s a real shame,” says Clare McCurdy, a history teacher who has accompanied the students from the Harris Academy Peckham. “Some of these kids are studying art, they’re really engaged and passionate about it.” Yet: “Before we came we asked the kids to draw a typical person who goes to the theatre or to art galleries and they mostly drew a white, middle-class woman in her fifties, with a name like Claudia.”

They were not far off the mark. Last summer the Audience Agency charity published the results of a survey, taking in 100 visual arts organisations across England. Although most are free, their visitors are still largely highly educated, affluent professionals, the report found. It concluded that understanding the barriers preventing those from disadvantaged or minority groups from visiting “remains one of the greatest challenges facing visual arts’’.

“It was at the forefront of what we talked about at the National Gallery when I started my career 20 years ago, and we had the same conversations about diversity and inclusion when I worked as a curator for the National Trust,” says Rebecca Lyons, the director of learning and collections at the RA.

There are, she points out, many ways to visit the RA free of charge. “We’ve got a new building, more free displays, a Collections Gallery that’s free to visit anytime. If you’re under 16, all exhibitions are free too . . . But that’s not the main barrier. The barriers to participation are so many and so complex.”

Critics Club aims to break barriers

While galleries struggle to address these barriers, a programme has been launched with the aim of breaking them down. Funded by its participant schools and partly by grants (including from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation), Critics’ Club operates like an independent after-school club, working with students that a school deems most in need of, or likely to benefit from, its programme.

In the course of eight weeks, these young people visit some of the capital’s most prestigious arts institutions, learning how to write persuasive and engaging critical reviews of the exhibitions and performances they see. There is, however, a second goal. To inculcate a lifelong sense of belonging in and enthusiasm for these spaces.

The Harris Academy group are on the inaugural trip of Critics’ Club’s first full, eight-week programme. As they funnel into the RA’s Eco-Visionaries exhibition, a couple of boys jostle and chatter distractedly.

“All young people love school trips,” Yasmin Ibison, the founder of Critics’ Club, says. “The challenge is conveying the message that these spaces are available and open to them outside those trips too. More affluent students will get their first introductions to traditional cultural spaces through their family.

“That means galleries and theatres become spaces that they see themselves reflected in and belonging in. They’ll understand how to navigate them, what the spoken and unspoken rules are in those places — because there are many.”

The teenagers take out their Critics’ Club notebooks and begin to draw pictures or take notes. A previously boisterous boy stands transfixed by a difficult, foreign-language video piece, long after the rest of the group have moved on.

There is a debate (and a little selfie-taking) in front of Basim Magdy’s Our Prehistoric Fate 2011, in which two lightboxes depict a dinosaur and the words “The Future Belongs to Us’’. “The dinosaurs didn’t expect to go extinct either, so they’re saying it could happen to us too,” 13-year-old Megan says. For the next hour, a focused enthusiasm settles over the group.

"I felt welcome when we arrived"

Back at school, two days later, Ibison sets the group a “free writing” exercise, encouraging them to write continuously for a minute, prompted by the opening phrase: “Before I went to the Royal Academy, I thought . . .’’. “I thought it would be boring,’’ more than one student writes, “but actually I learnt a lot.”

“I thought it was a fancy place, too fancy for us,” Megan says, hinting at the possibility that architecture and a building’s name can deter first visits (it is the Royal Academy after all). “But actually, I felt welcome when we arrived. And when we went into the exhibition, I felt really connected to it because climate change is something I really care about. Yeah, I’d definitely go back.”

Ibison’s data suggests she might. “When we measure the extent to which the programme makes them want to engage more with arts and culture, 89 per cent agree or strongly agree. When we ask to what extent they agree or disagree that Critics’ Club made them feel empowered to express their opinions, 81 per cent agree or strongly agree.”

Olamide Taiwo, 17, was one of the first students to test Ibison’s programme, while she was developing Critics’ Club at a south London state school in 2018. “I have always been interested in seeing plays at the theatre and going to art galleries, but at the same time I did not believe it would be my type of scene,” Taiwo says, “because when I go to these places I do not see people that look like me so I get impostor syndrome. The Critics’ Club was a place where I could go to enjoy these wonderful forms of art with people from similar backgrounds.”

She is convinced that there are serious academic advantages to engaging with the arts. In fact, she has just been given a conditional offer to study classics at Oxford. “My writing skills seriously improved due to the reviews we had to write after every trip,” she says.

However, she sees wider value in the programme too: “I learnt that these spaces are not just for rich white people, but for everyone.”

"Galleries should recruit within the communities they need to attract."

Ibison’s view is that the arts institutions most successful in attracting and keeping a diverse range of visitors “have those communities embedded into the organisation”. For example: “If your youth board is made up exclusively of young people whose wealthy, well-connected parents have encouraged them to apply, then you can expect that board to make decisions that will attract more people like them.”

Instead, galleries should recruit actively within the communities they most need to attract: “You’ve got to go out to them, rather than expecting them to come through the door just because it’s free.”

“They should advertise on YouTube and the social media channels that young people use,” 13-year-old Umar says. “I’d definitely go back now I know what it’s like.”

“Or they could advertise in schools so we actually know about them,” Joel suggests, as he finishes his first review as a fledgling art critic. “It was my birthday four days before the trip. Actually, it was the first art gallery I have been to. And it was the biggest present.”

Critics’ Club is looking for more schools with which to collaborate. To find out more visit criticsclub.org or tweet @critics_club.

This article by Hattie Garlick originally appeared in The Times. Pictures by Grey Hutton for The Times.